Looking deeper into the Clery Act: An ‘abbreviated snapshot’ of crimes on FMU’s campus

Photo by: Contributed Graphic Edited by Sydney Hogg

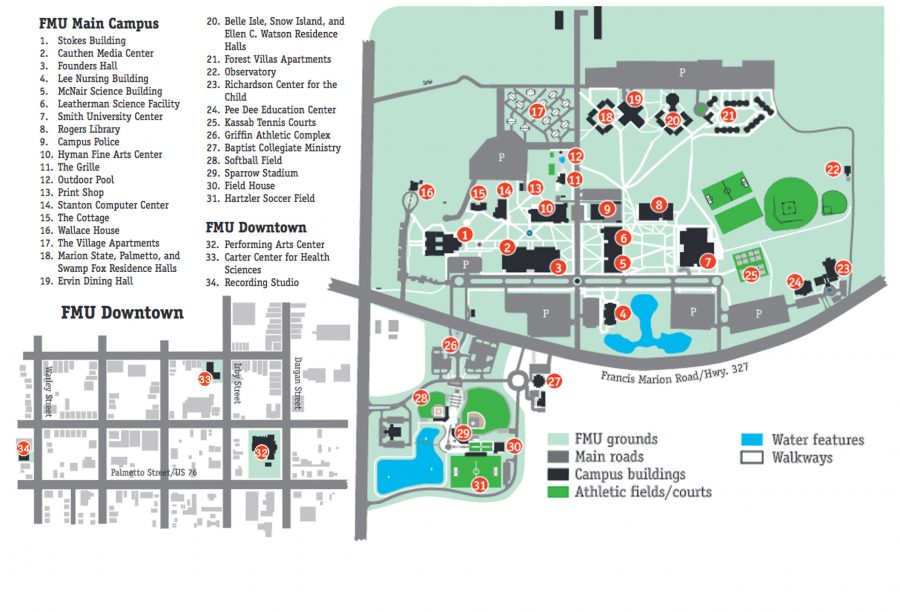

The above graphic shows the reportable geography for FMU’s campus, including the downtown facilities. Any crimes that appear in the Clery Act took place on FMU’s reportable geography.

Since 2013, FMU has reported only two cases of sexual assault and four of dating violence on its annual crime transparency report. Geography, number of students living on campus, definitions and fact checking are just a few of the factors that contribute to the unusually low numbers.

The annual crime transparency report is available to all students, and at FMU, it’s available both online and at the Campus Police Station. Its official name is the Jeanne Clery Disclosure of Campus Security Policy and Campus Crime Statistics Act, but it’s commonly referred to as the Clery Act, named for a former student of LeHigh University – Jeanne Clery.

History

According to the Clery Center, when Clery was a student in 1986, she was raped and murdered in her dorm room. Her assailant was another student at the university. Clery’s parents discovered that students were reporting crimes, such as sexual assault, to campus police, but they weren’t sharing information with students about the crimes. It was important to get out the information so that students could take any protections they needed to stay safe on campus. After that, the Clerys devoted their time to making sure there was a uniform way to report crimes to students. Thus, the act was put into law in 1991.

The Handbook for Campus Safety and Security Reporting 2016 (Handbook) said the Clery Act is a federally mandated report that all universities receiving federal funding must create each year.

The Clery Act requires universities to disclose their policies in several areas, including emergency alert procedures, disciplinary actions for certain crimes and counting crime statistics. Congress passed the requirement of the report in 1991 and amended it in 2013 to incorporate dating violence, domestic violence and stalking in the crime statistics, using the definitions of the 1994 Violence Against Women Act (VAWA), according to the Handbook.

Geography

Only crimes that take place within a certain area or geography are required to be reported in the Clery Act. It’s crucial to understand what FMU’s reportable geography is to properly interpret the statistics.

The Handbook is very clear about what crimes must be reported based on their location. If a sexual assault takes place at an off-campus location, it would not be reportable, according to the Handbook. If a girl was being violently abused by her boyfriend in Patriot Place Apartments, that incident would not be reportable, even if both parties are students.

More specifically, according to the Handbook, the definition of FMU’s geography is “any building or property owned or controlled by an institution within the same reasonably contiguous geographic area and used by the institution in direct support of, or in a matter related to, the institution’s educational purposes, which includes residence halls; and any building or property that is within or reasonably contiguous to the area … that is owned by the institution but controlled by another person, is frequently used by students, and supports institutional purposes.”

In other words, any crimes taking place in any building or area owned by the university or that the university has a written agreement with have to be shown on the Clery Act.

This is important to know, especially when looking at FMU’s Clery Act, because U.S. News and World Report says that only 45 percent of students live on campus. Annie Clark, the executive director of End Rape on Campus, said it’s important to remember geography and university size when interpreting the numbers.

“Not having sexual assaults just statistically doesn’t happen,” Clark said. The statistics that Clark referred to show a serious contrast with what FMU reports each year. Statistics from the National Sexual Violence Resource Center show that in 2015 one in five women were sexually assaulted while in college, which doesn’t seem to be the case at FMU.

It goes back to the geography of the incident. The sexual assault, or dating violence, domestic violence, stalking, etc., must have occurred on FMU’s reportable geography for it to show on the Clery Act.

Not having sexual assaults just statistically doesn’t happen.

— Annie Clark, Executive Director of End Rape on Campus

Defining the crime

After Campus Police receive a report, the next step is to look at each case to see if it meets the definition of a reportable crime.

The definition for sexual assault that must be used for Clery Act reportable crimes is included in the Handbook. The definitions for dating violence, domestic violence and stalking are from the VAWA.

In brief, the Handbook says the definition of sexual assault is any act committed against another person without their consent or their ability to give consent. There are four subcategories of sexual assault: rape, incest, fondling and statutory rape.

Domestic violence, according to the Handbook, is a crime of violence that is committed by a person who lives with another as “a spouse or intimate partner,” someone with a familial relationship or someone who has a child with the victim. Domestic violence is specific in that it does not apply to roommates, and since more often than not roommates at FMU don’t have familial or intimate relationships with each other while cohabitating, this is usually not a problem on campus.

According to the Handbook, the definition of dating violence is “violence committed by a person who is or has been in a social relationship of a romantic or intimate nature with the victim.”

Stalking is “engaging in a course of conduct directed at a specific person that would cause a reasonable person to fear for the person’s safety or the safety of others or to suffer substantial emotional distress.” By this definition, there has to have been two or more acts, which include acts through third parties and over any medium of communication, as seen in the Handbook.

Campus Police Chief Donald Tarbell said FMU used both the definitions from the Clery and VAWA but also refers to the government’s uniform reporting code and the national incident based reporting system (NIBRS).

“The FMU Police Department follows crime and incident reporting procedures [that] are nearly universal to law enforcement in South Carolina and the United States,” Tarbell said. “None of these systems, and the definitions that support them, allow much room for interpretation.”

Alison Kiss, executive director of the Clery Center, confirmed that campus police should use both NIBRS and Clery Act definitions, especially since they are so similar.

“The statistics should be compiled using the definitions in the Clery regulations,” Kiss said. “These definitions are consistent with uniform crime reporting, VAWA definitions (dating violence, domestic violence and stalking). Drug, weapon and liquor referrals and arrests are based on state laws.”

The FMU Police Department follows crime and incident reporting procedures [that] are nearly universal to law enforcement in South Carolina and the United States. None of these systems, and the definitions that support them, allow much room for interpretation.

— Campus Police Chief Donald Tarbell

Several organizations, though, said that there can be a “gray zone” in the interpretation of a crime, but others disagreed. The gray zone, in this instance, would be the degree of interpretation that the Clery compiler has when looking at each situation to decide if it should show on the crime statistics.

Tarbell said that since the definitions are so narrow, there’s very little way to interpret a situation to see if it does or does not meet the definition of a Clery reportable crime.

“If there is a ‘gray area’ it can be found at the very beginning of the process when an officer produces a report from the field,” Tarbell said. “When there are questions regarding the classification of a particular event, that incident is reviewed by multiple supervisors in our department, and, if necessary, beyond.”

Frank LoMonte from the Student Press Law Center said that the gray zone is whether a report constitutes being a crime.

LoMonte gave the example of a student hitting another student in the arm jokingly with a soft-cover book versus a student hitting another student multiple times in the head with a thick, hardcover book. The question of intent comes into play, and campus police have to use their discretion from the training they’ve received to figure out how to code it.

The coding is important because the code determines how a report will be cataloged. Since FMU uses both NIBRS and Clery definitions, the code assigned to a report help campus police pull up the reports they need when compiling the statistics.

The Clery Act is clear that the only reason an incident report wouldn’t show up on the Clery Report is if it is unfounded. The Handbook says the only way a report can be unfounded is “if sworn or commissioned law enforcement personnel make a formal determination that the report is false or baseless.”

Additionally, the Handbook says, “A reported crime cannot be designated ‘unfounded’ if no investigation was conducted or the investigation was not completed. Nor can a crime report be designated unfounded merely because the investigation failed to prove that the crime occurred; this would be an inconclusive or unsubstantiated investigation.”

Annie Clark, executive director of End Rape on Campus, said the only reason that a reportable offense wouldn’t show up on the Clery Act should be because it is unfounded. Clark said the officer must have a reasonable belief that the case is a lie.

An example Clark gave was of an individual coming into the campus police station to report a mass murder on campus. If the mass murder did not happen, the claim wouldn’t have to go on the Clery Act.

Regardless of the evidence or lack there of to support a claim, the crime should appear in the statistics if it was reported with the exception of it being unfounded.

“You don’t need to have physical bruises to be a victim of abuse,” Clark said.

Fact-Checking the Clery Act

Tarbell said that FMU has several people who review the report before it gets published.

“The Clery Report itself is reviewed by several university officers, not associated with the police department, prior to its publication,” Tarbell said. “This includes review by the General Counsel of the university, the university’s Title IX Coordinator, the university’s Dean of Students, and the university Housing Director. A deliberate misrepresentation of facts would require too broad a coalition of participation, so broad, in fact, as to render that circumstance extremely unlikely.”

But Title IX Coordinator Dr. Charlene Wages, Dean of Students Theresa Ramey and Housing Director Cheryl Tuttle said they only receive the police reports that relate to their fields.

Wages said she receives police reports pertaining to Title IX issues. Ramey said she receives reports concerning FMU’s community and conduct. Tuttle said she receives police reports about housing issues or anything that happens in housing.

General Counsel Jonathan Edwards did not respond in time for his comments to be included.

Wages, Ramey and Tuttle all said that they do not look at every single police report that campus police has.

Ramey said that she is not the check-and-balance of the university, and she said she trusts Chief Tarbell’s training and the training of the other officers have to report police cases correctly.

Ramey said she looks at the whole Clery Act, but mainly she focuses on the policy section, making sure it matches the Handbook.

“There’s an email that goes out to all the advisors [of student organizations] … if you have any information that fits those crimes [included on the Clery Act],” Ramey said. “What we do is we give information and then what they have to do is make sure it fits the criteria for what the crime is.”

Tuttle checks and updates residential facilities and policies.

“[The crime statistics page] would be picked up [by campus police] because they see all the crime,” Tuttle said. “Campus police would be involved anyhow, so they can pick that up from their own data. I don’t see that until it’s printed. [Tarbell] wouldn’t ask me, for example, if we had 20 arrests of drug use because he would have the most accurate information. I would not.”

LoMonte said that fact checking is an important, yet often overlooked, aspect of the Clery Act.

“It does raise the question particularly about who’s checking behind these universities, and I think that’s really the bigger and better question,” LoMonte said. “Is anyone going back and auditing these universities to see if they are miscategorizing crimes or purposefully downgrading them or omitting them from the reports. We really are on the honor system right now. It really is a matter of trusting the record keeper.”

LoMonte said that universities do have a motive to keep their numbers low to seem safer, which Clark said is a red flag in and of itself because it may look safer, but a university has a motive to lie to its students. LoMonte said that often universities think if the crime statistics appear low, it gives the university an image of being a safe place.

“Nobody wants to be known as a place with a lot of crime, so there really is a great question to be asked whether universities can be trusted to be the sole decision makers here,” LoMonte said. “There’s a very infrequent auditing that goes on at the U.S. Department of Education, so everybody knows that you’re highly unlikely to be audited, and even if you are, the penalties are quite rare.”

Organizations such as the Clery Center and End Rape on Campus won’t make comments on any specific cases for legal reasons. To receive external reviews on reports, The Patriot would have had to hire a lawyer or file a formal complaint with the U.S. Department of Education.

Nobody wants to be known as a place with a lot of crime, so there really is a great question to be asked whether universities can be trusted to be the sole decision makers here.

— Frank LoMonte, Student Press Law Center

Explaining FMU’s low numbers

If the most current statistic is that one in five women are raped while in college, the question can’t be avoided – why were there only two sexual assaults since 2013?

This is the part where understanding Clery Act geography becomes so vital. Less than half of our students live on campus.

FMU has strict liquor policies, which can be seen in the FMU Catalog 2016-2017, so there’s the expectation that less drinking takes place on campus. According to the National Institute of Justice, at least half of sexual assaults at colleges occur after any or both individuals drink alcohol. Part of the definition of sexual assault is that the victim isn’t capable of giving consent, so if the victim is under the influence of alcohol or drugs, they can’t give consent, according to Rape, Abuse and Incest National Network. Such strict liquor policies on campus decrease the chance of a sexual assault taking place on campus.

Another potential explanation of FMU’s low numbers could be a low reporting rate. If students don’t go to campus police to report a stalking, dating violence or sexual assault issue, then campus police don’t know about it, and they can’t help the victims or show it on the Clery Act.

Clark said that there are two reasons that students might not go to campus police to report a crime, both of which are red flags. First, Clark said that students may feel uncomfortable reporting a sexual assault to campus police. It’s a sensitive subject, and students need to feel safe and comfortable when opening up about a sexual assault. Second, she said students may be unsure where to go or to whom to report crimes. Clark said some students may not know which officer to talk to or if they should go to their resident assistant or a professor.

The Patriot requested every police report since 2012 that wasn’t a criminal report, including reports such as students coming in for their concerns, property damage, fire alarms and traffic violations. Out of the several hundreds of reports, only a few were concerns that students had and weren’t for issues such as property damage, fire alarms or off-campus threats. By reviewing the reports, it seemed as if students went to campus police to make complaints about roommate disputes or he-said-she-said arguments rather than sexual assaults.

Is the Clery Act a useful tool?

LoMonte called the Clery Act an “abbreviated snapshot” of crime at any university. There are so many variables that go into the Clery Act, such as geography, students reporting and accuracy of the report, that it’s impossible to say that it is either not useful or useful.

The U.S. Department of Education is in charge of all Clery Act audits and complaints. If any student has questions or complaints about FMU’s Clery Act, they can email the U.S. Department of Education at clerycomplaints@ed.gov or call 1-800-4-FED-AID.