Sometimes, it’s okay to be okay: The dangers of romanticizing illness

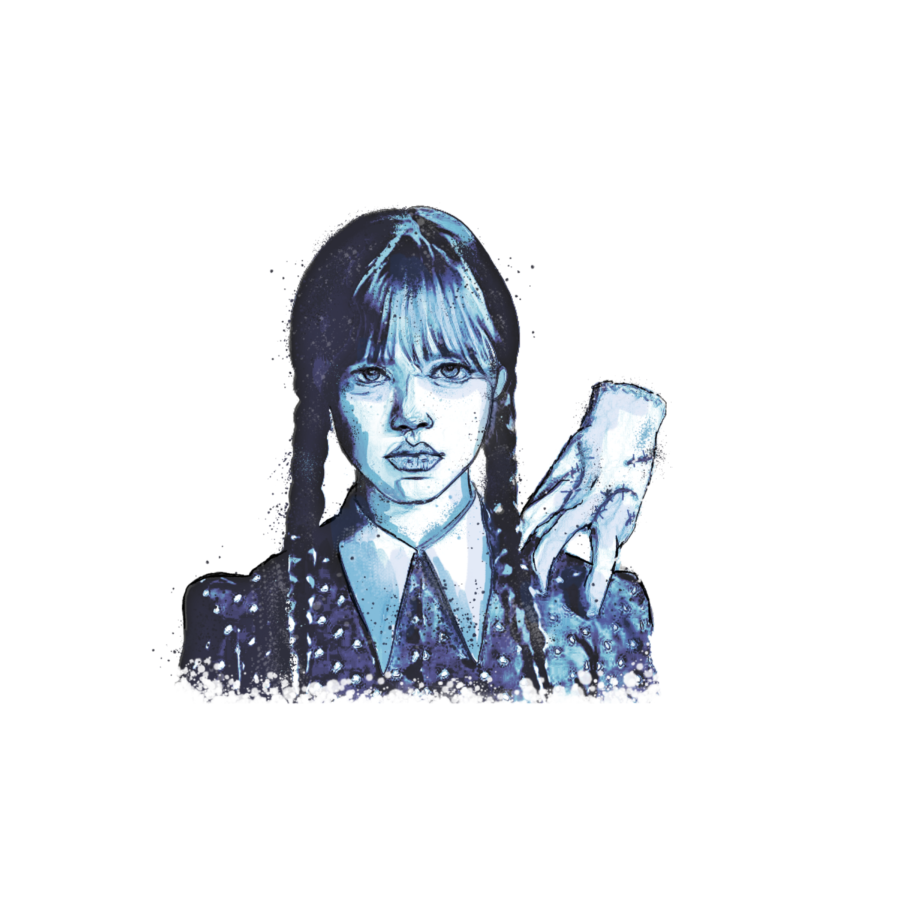

Photo by: MaKayla O’Neal

To say the absolute least, we live in odd times.

As social media grows to basically consume our entire livelihoods, we’re seeing a lot of global movements come and go. However there have been a few that have snowballed consistently through the years, such as the mental health movement, and its counter partner, the mental disorder movement.

I have heard a lot of older generations make the common complaint that young adults and even children in current days “all want to be mentally ill”. I would like to explore the legitimacy of the comment, and the dangers it could bear to the actually diagnosed.

First and foremost, I would like to bring up the label neurodivergent.

You have probably heard this word being thrown around a lot, especially with the label trending on social media platforms. In a nutshell, neurodivergent disorders refer to people whose brains process things differently. There doesn’t seem to be an official definition of either neurodiversity or neurodivergent; however, most articles on the movement focus on neurological conditions like ADHD, dyslexia, or autism.

The term “neurodiversity” was first used by autism rights activist Judy Singer.

“[It] articulate[d] the needs of people with autism who did not want to be defined by a disability label but wished to be seen instead as neurologically different,” Singer said.

So why is it we are seeing these terms being thrown around constantly and almost carelessly?

Though I believe many people do not ‘want’ to be mentally ill, behaving in a way that suggests mental illness might be the best method to appear unique or emotionally complex or deserving of love and attention. I cannot blame anyone who thinks in this fashion because of the abject romanticization of these behaviors in the media today.

Many speculate that popular characters from trending shows and movies are becoming faces for mental disorders. Two major examples would be Wednesday Addams from the Wednesday series and Eddie Munson from Stranger Things, who have been diagnosed with autism by their fanbase.

Looking on the bright side, having these characters represent neurodiversity could be a huge platform to diminish judgment against mental disorders. On the other hand, it also casts weary sighs from those actually living with disorders because it seems like an obnoxious attempt to romanticize their struggles, and it will not lead to a deeper understanding.

This goes further into the ideology that people want to be something without actually having to experience it. It’s quite an easy thing to assume that any impressionable person being exposed to these characters, and the massive amount of love they receive on the internet, will almost take on the persona of disorders as a way to join the “edgy” bandwagon.

This leads to the controversy found today regarding self-diagnosis and having media act as a placebo for mental illness. While this is an entirely possible reality, I do want to acknowledge other major circumstances happening that are scientifically leading to influx of mental health diagnoses.

Research done through the CDC points that the total number of mental, behavioral and neurodevelopmental diagnoses increased by 30% between 2018 and 2021. One major villain in that statistic is, as you probably guessed, social media.

I am a part of the generation that had the privilege to grow up without social media until my teen years, where I was bombarded with the media. I would be lying through my teeth if I were to say it did not impact my own mental well-being until I learned to control my intake. With that being said, I can’t even imagine how even younger generations feel as they grow up in this life draining spectacle.

A broad study done through the United Nations Mental Health and Development claimed six out of 10 Americans are negatively affected by social media. This just shows that the proclamation that “everybody is depressed ,anxious, etc.” is not far off of reality.

If you have taken away nothing else from this writing, let my concluding statement register: be kind.

You cannot dictate (unless you happen to be a licensed professional) what is going through another’s mind. We should refrain from passing judgment on someone’s presentation of a potential mental illness without knowing virtually everything about them and their life.

So many people who actually have mental illnesses end up suffering when neurotypical people and other people with mental illness tell them that they’re faking it; and even if they aren’t, someone needs to let them know in a non-antagonistic way that there are other ways to ask for help or attention without fabricating an illness they don’t qualify for based on semi-arbitrary standards.

Please remember that only licensed professionals have the authority and educational background to diagnose people with a mental health disorder. FMU offers free consultations through the Counseling and Testing Center with an entire group of mental health professionals. You can find more information about this resource through the FMU website at https://www.fmarion.edu/counselingandtesting/counseling/.